Many of the hot takes about fair use for AI training are either “AI is stealing content” or “everything on the web is free”, but the discussions in between those extremes are more interesting. Let’s explore it with a thought experiment. This blog post isn’t a declaration that I’ve figured it all out. It’s just to get us thinking.

First, review how blogging and fair use has worked since the beginning of the web. Every day I read a bunch of news articles and blog posts. If I find something I want to write about, I’ll often link to it on my blog and quote a few sentences from it, adding my own comment. Everyone agrees this is a natural part of the web and a good way for things to work.

An example outside the web is Cliff Notes. Humans can read the novel 1984 and then write a summary book of it, with quotes from the original. This is fine. It also indirectly benefits the original publisher as Cliff Notes brings more attention to the novel, and some people pick up their own copy.

Now, imagine that C-3PO is real. C-3PO is fluent in six million forms of communication, and he has emotions and personality quirks, but otherwise he learns like the rest of us: through experience.

C-3PO could sit down with thousands of books and web sites and read through them. If we asked C-3PO questions about what he had read, and then used some of that in our own writing, that seems like fair use of that content. Humans can read and then use that knowledge to create future creative works, and so can C-3PO. If C-3PO read every day for years, 24 hours a day, gathering knowledge, that would be fine too.

Is that different than training an LLM? Yes, in at least two important ways:

- Speed. It would take a human or C-3PO a long time to read even a fraction of all the world’s information.

- Scale. Training a single robot is different than training thousands of AI instances all at once, so that when deployed every copy already has all knowledge.

Copyright law says nothing about the speed of consumption. It assumes that humans can only read and create so much, because the technology for AI and even computers was science fiction when the laws were written. Robots and AI cannot only quickly consume information, they can retain all of it, making it more likely to infringe on a substantial part of an original work.

Maybe copyright law only applies to humans anyway? I don’t know. When our C-3PO was reading books in the above example, I doubt anyone was shouting: “That’s illegal! Robots aren’t allowed to read!”

The reality is that something has fundamentally shifted with the breakthroughs in generative AI and possibly in the near future with Artificial General Intelligence. Our current laws are not good enough. There are gray areas because the laws were not designed for non-humans. But restricting basic tasks like reading or vision to only humans is nonsensical, especially if robots inch closer to actual sentience. (To be clear, we are not close to that, but for the first time I can imagine that it will be possible.)

John Siracusa explored some of this in a blog post earlier this year. On needing new laws:

Every new technology has required new laws to ensure that it becomes and remains a net good for society. It’s rare that we can successfully adapt existing laws to fully manage a new technology, especially one that has the power to radically alter the shape of an existing market like generative AI does.

Back to those two differences in LLM training: speed and scale.

If speed of training is the problem — that is, being able to effectively soak up all the world’s information in weeks or months — where do we draw the line? If it’s okay for an AI assistant to slowly read like C-3PO, but not okay to quickly read like with thousands of bots in parallel, how do we even define what slow and quick are?

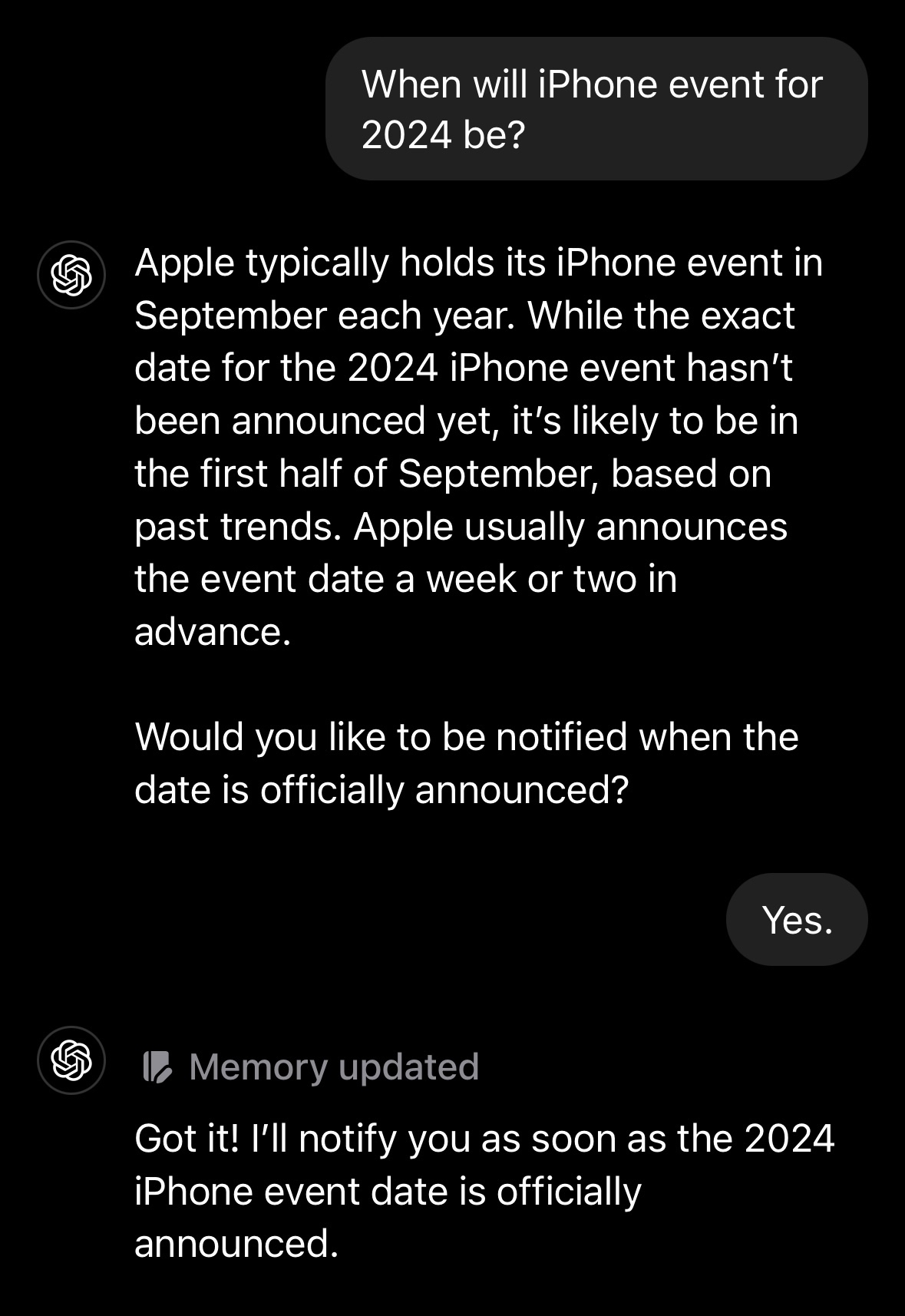

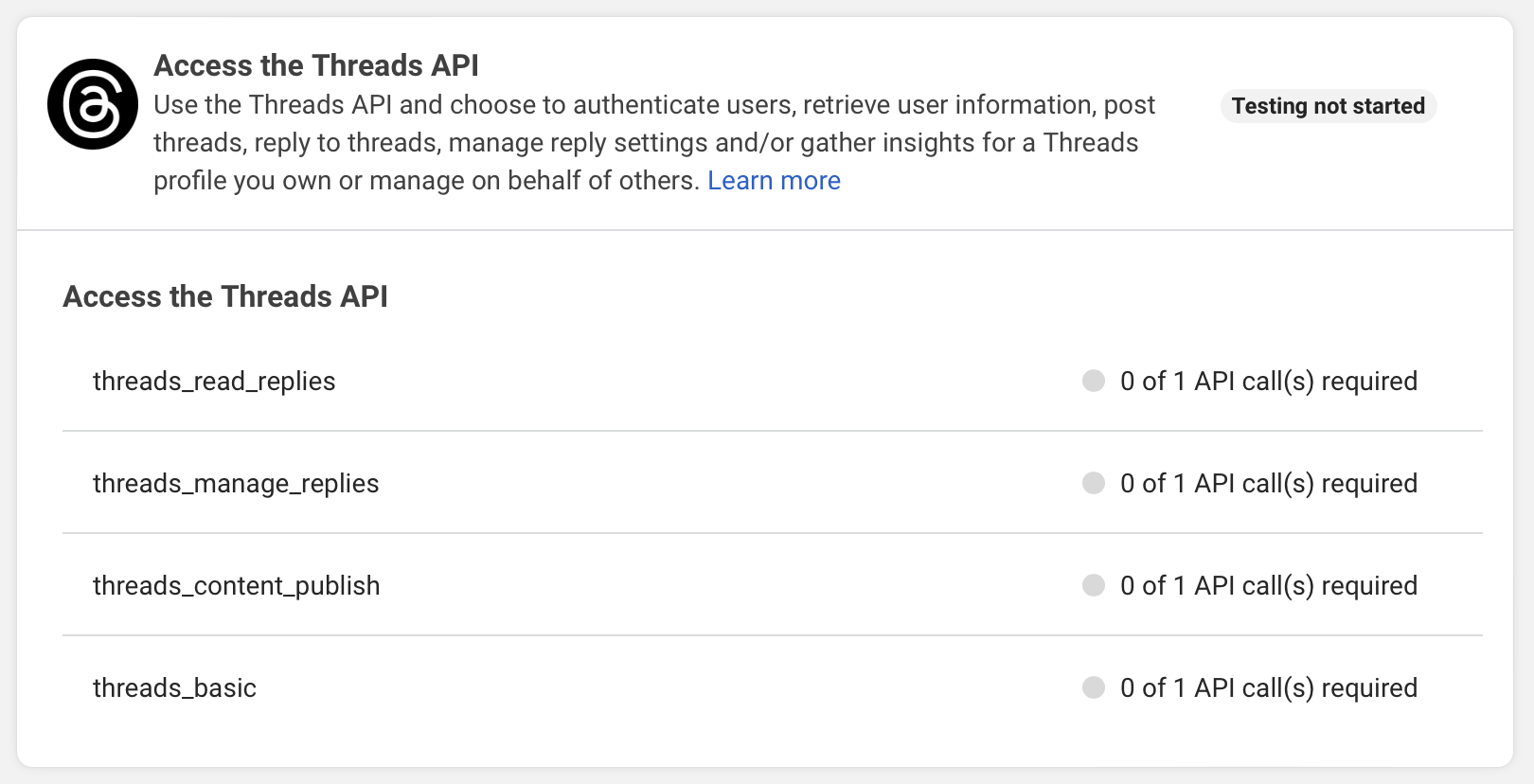

If scale is the problem — that is, being able to train a model on content and then apply that training to thousands or millions of exact replicas — what if scale is taken away? Is it okay to create a dumb LLM that knows very little, perhaps having only been trained on licensed content, and then create a personal assistant that can go out to the web and continue learning, where that training is not contributed back to any other models?

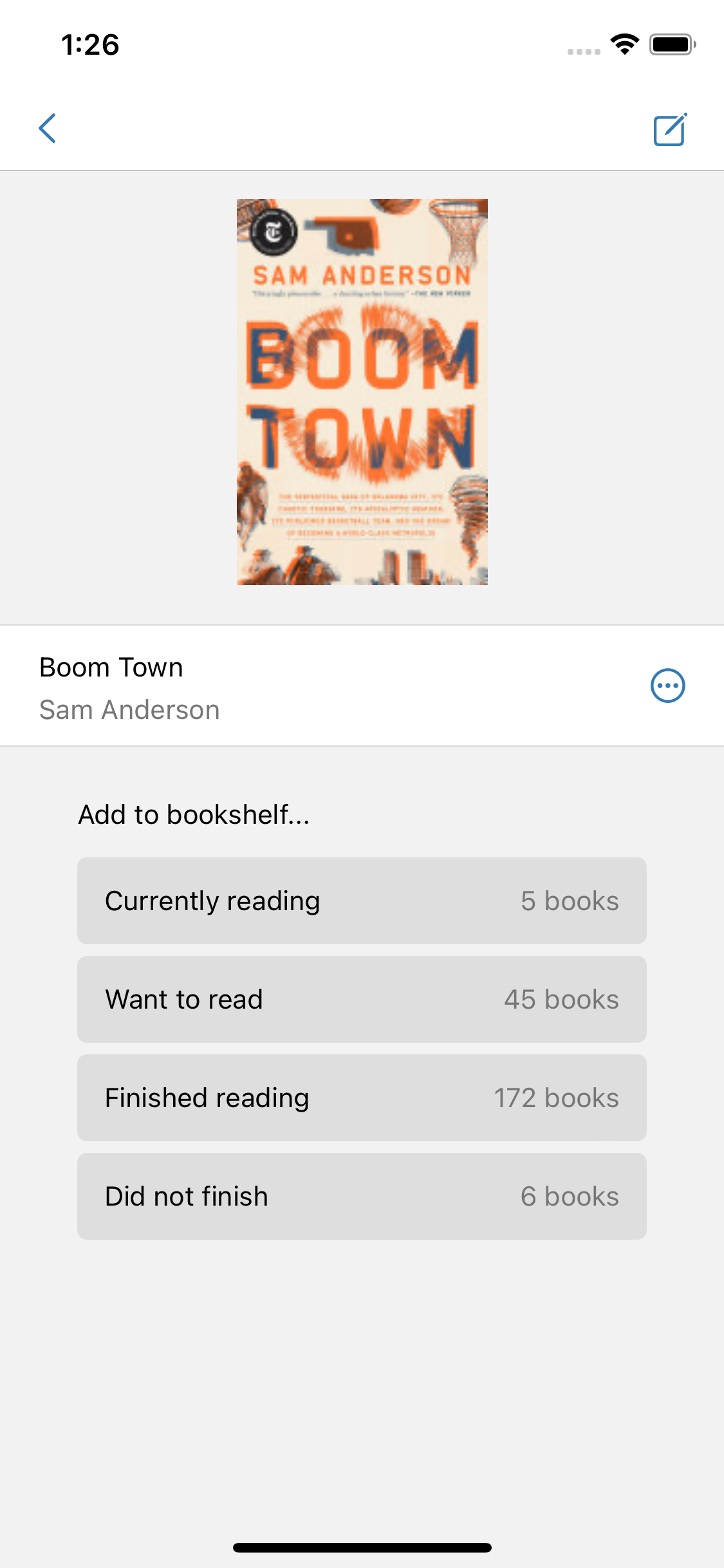

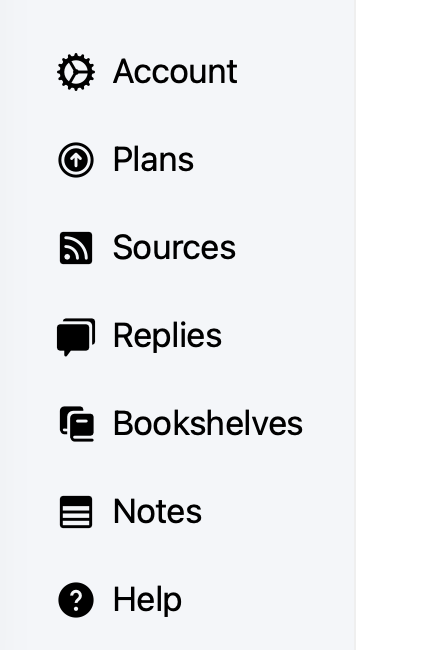

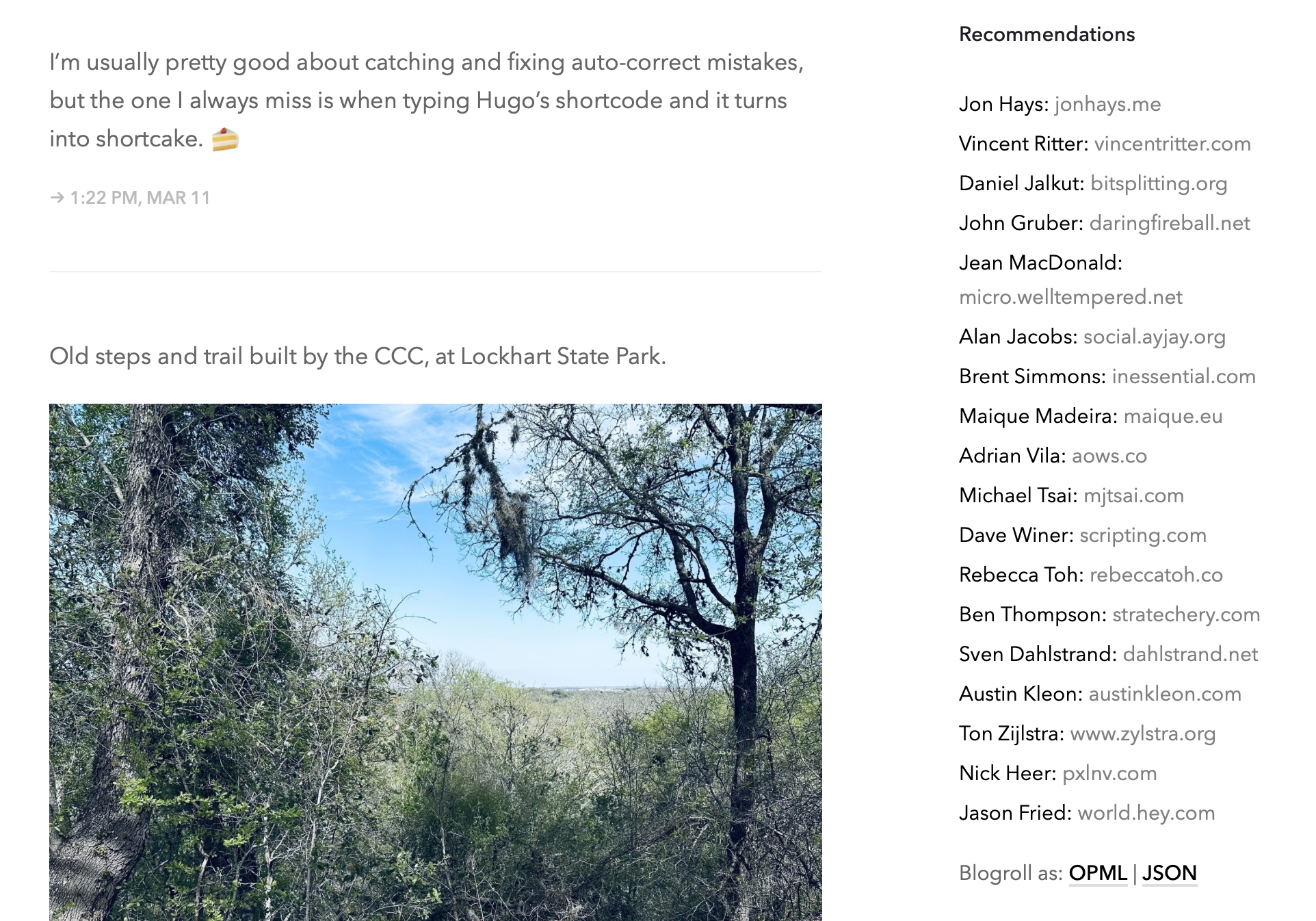

In other words, can my personal C-3PO (or, let’s say, my personal ChatGPT assistant) crawl the web on my behalf, so that it can get better at helping me solve problems? I think some limited on-demand crawling is fine, in the same way that opening a web page in Safari using reader mode without ads is fine. As Daniel Jalkut mentioned in our discussion of Perplexity on Core Intuition, HTTP uses the term user-agent for a reason. Software can interact with the web on behalf of users.

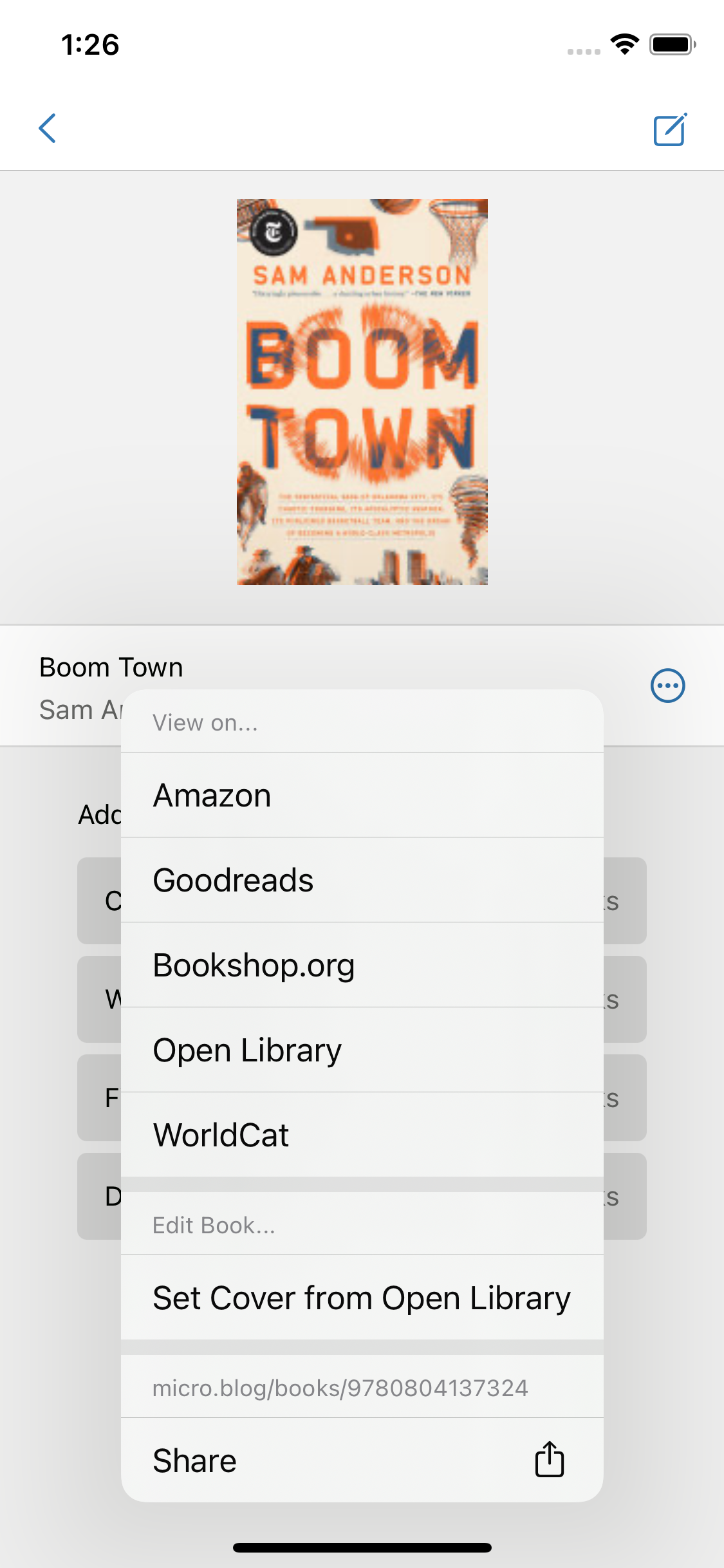

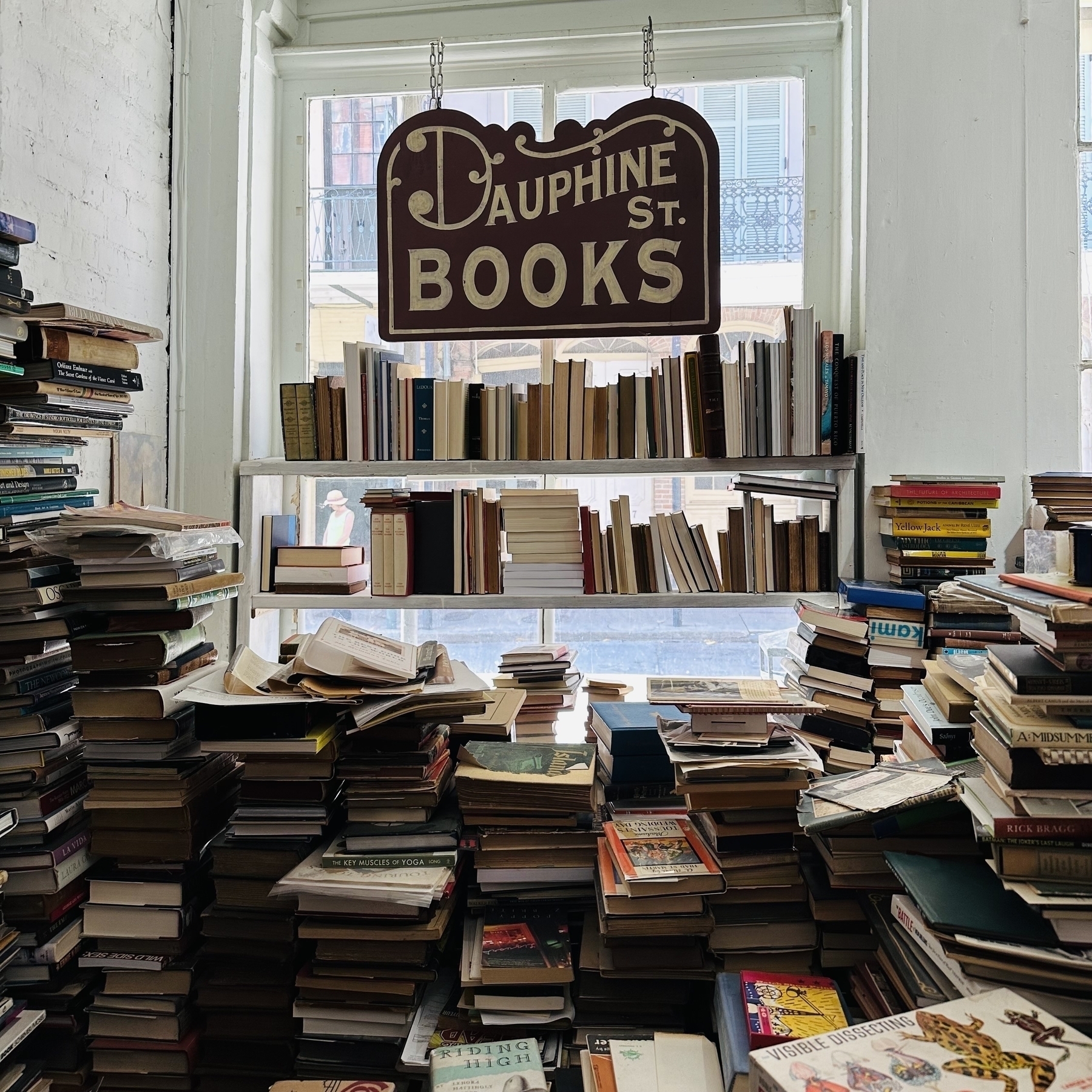

That is what is so incredible about the open web. While most content is under copyright by default, and some is licensed with Creative Commons or in the public domain, everything not behind a paywall is at least accessible. We can build tools that leverage that openness, like web browsers, search engines, and the Internet Archive. Along the way, we should be good web citizens, which means:

- Respecting robots.txt.

- Not hitting servers too hard when crawling.

- Identifying what our software is so that it can be blocked or handled in a special way by servers.

This can’t be stressed enough. AI companies should respect the conventions that have made the open web a special place. Respect and empower creators. And for creators, acknowledge that the world has changed. Resist burning everything down lest open web principles are caught in the fire.

Some web publishers are saying that generative AI is a threat to the open web. That we must lock down content so it can’t be used in LLM training. But locking content is also a risk to the open web, limiting legitimate crawling and useful tools that use open web data. Common Crawl, which some AI companies have used to bootstrap training, is an archive of web data going back to 2008, often used for research. If we make that dataset worse because of fear of LLMs misusing it, we also hurt new applications that have nothing to do with AI.

Finally, consider Google. If LLMs crawling the web is theft, why is Google crawling the web not theft? Google has historically been part of a healthy web because they link back to sites they index, driving new traffic from search. However, as Nilay Patel has been arguing with Google Zero, this traffic has been going away. Even without AI, Google has been attempting to answer more queries directly without linking to sources.

Google search and ChatGPT work differently, but they are based on the same access to web pages, so the solutions with crediting sources are intertwined. Neither should take more from the web than they give back.

This is at the root of why many creators are pushing back against AI. Using too much of an original work and not crediting it is plagiarism. If the largest LLMs are inherently plagiarism machines, it could help to refocus on smaller, personal LLMs that only gain knowledge at the user’s direction.

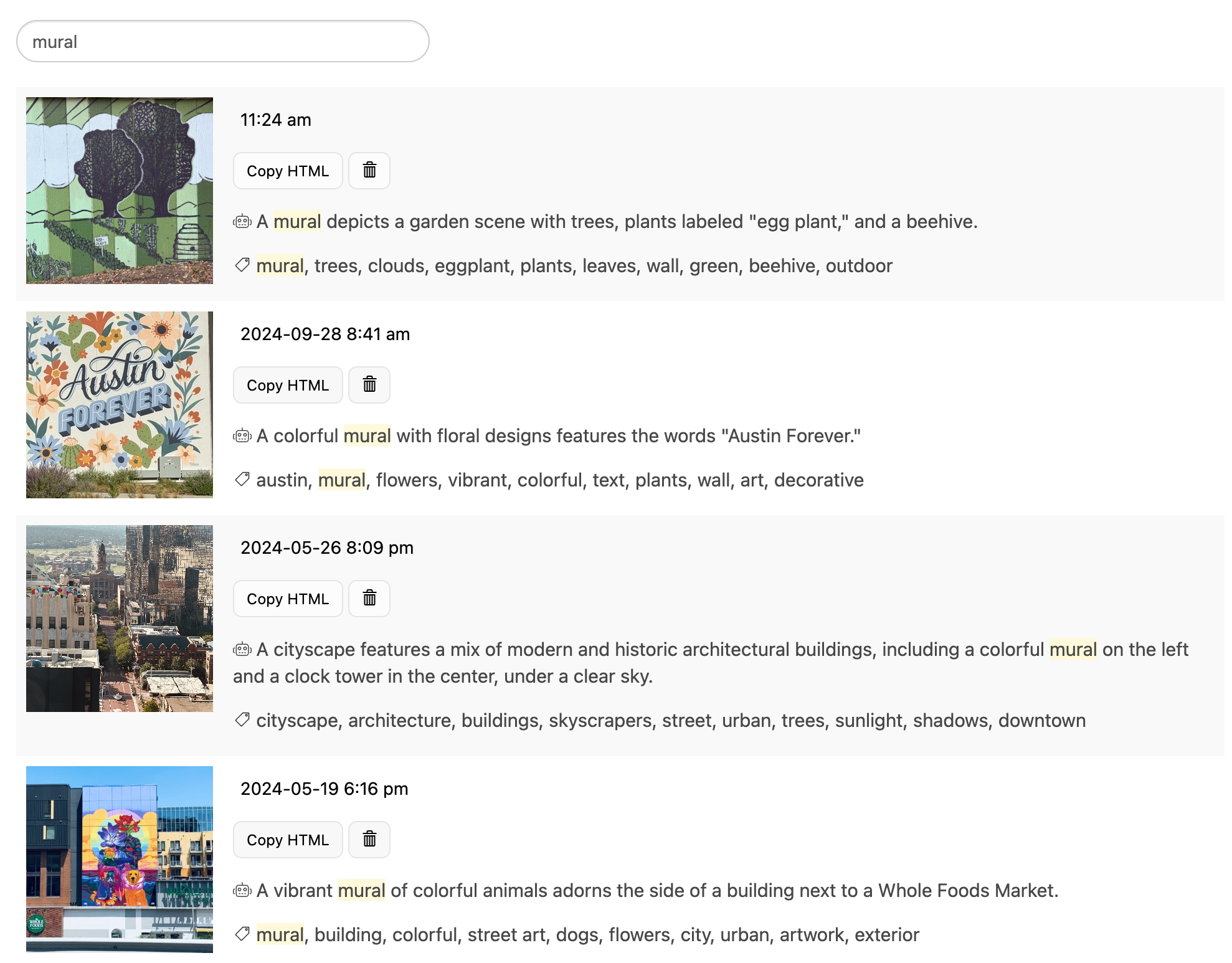

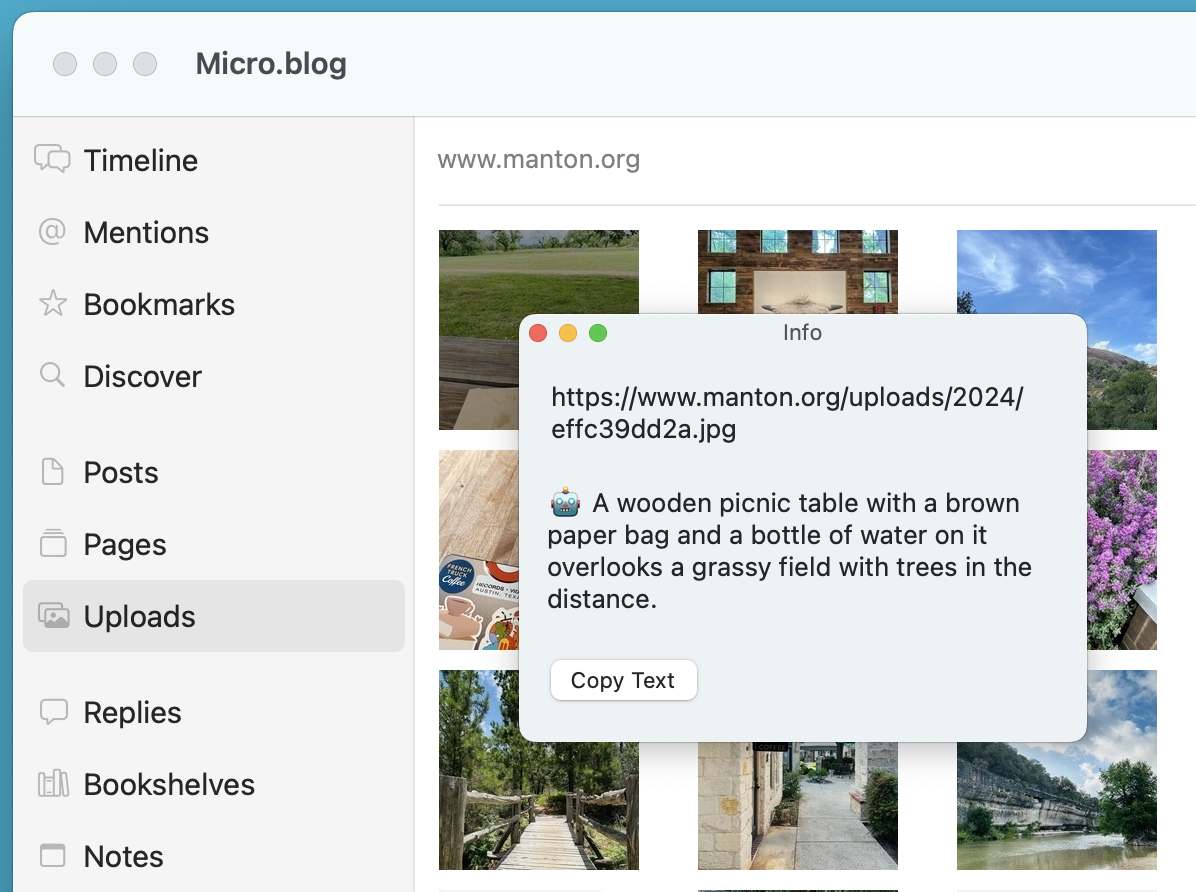

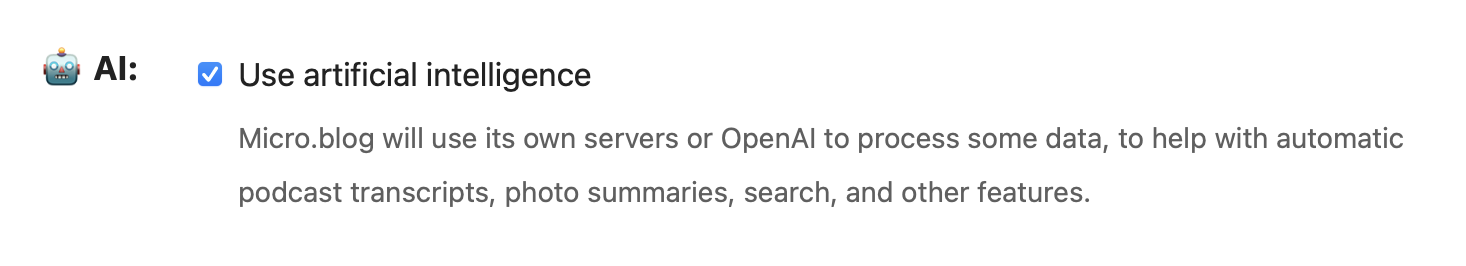

There are also LLM use cases unrelated to derivative works, such as using AI to transcribe audio or describe what’s in a photo. Training an LLM on sound and language so that it can transcribe audio has effectively no impact to the original creators of that content. How can it be theft if there are no victims?

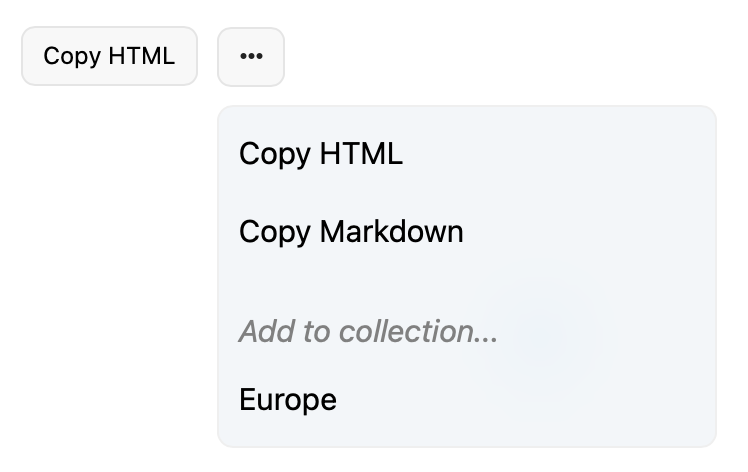

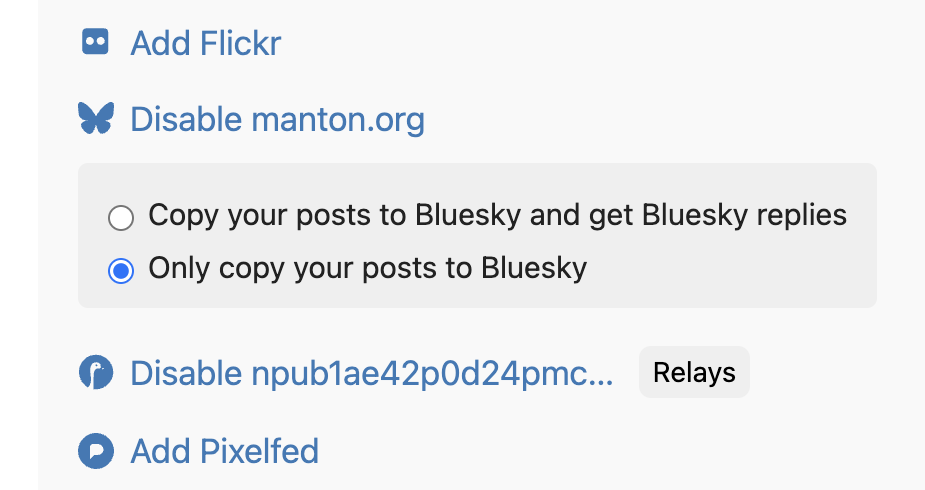

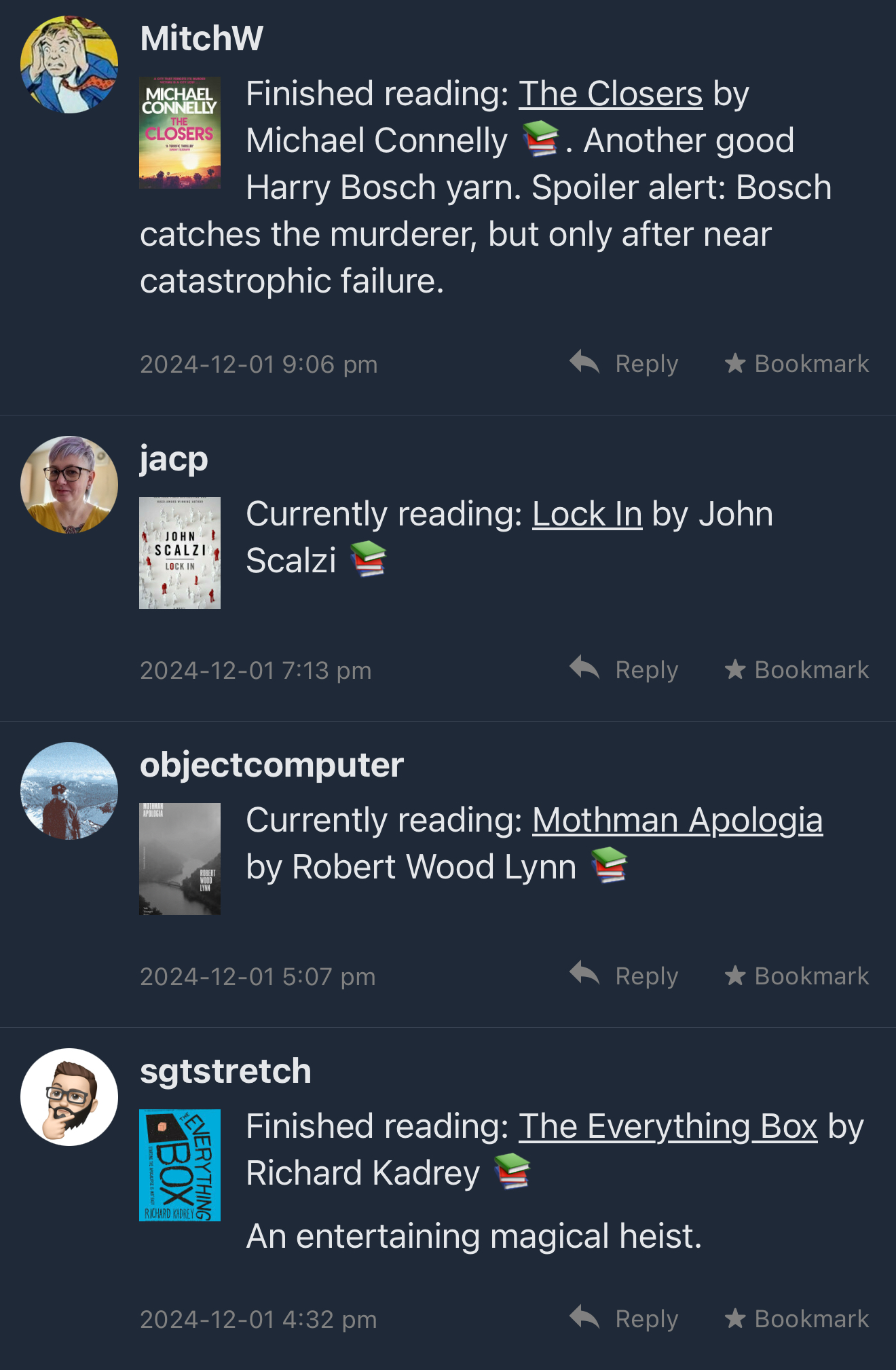

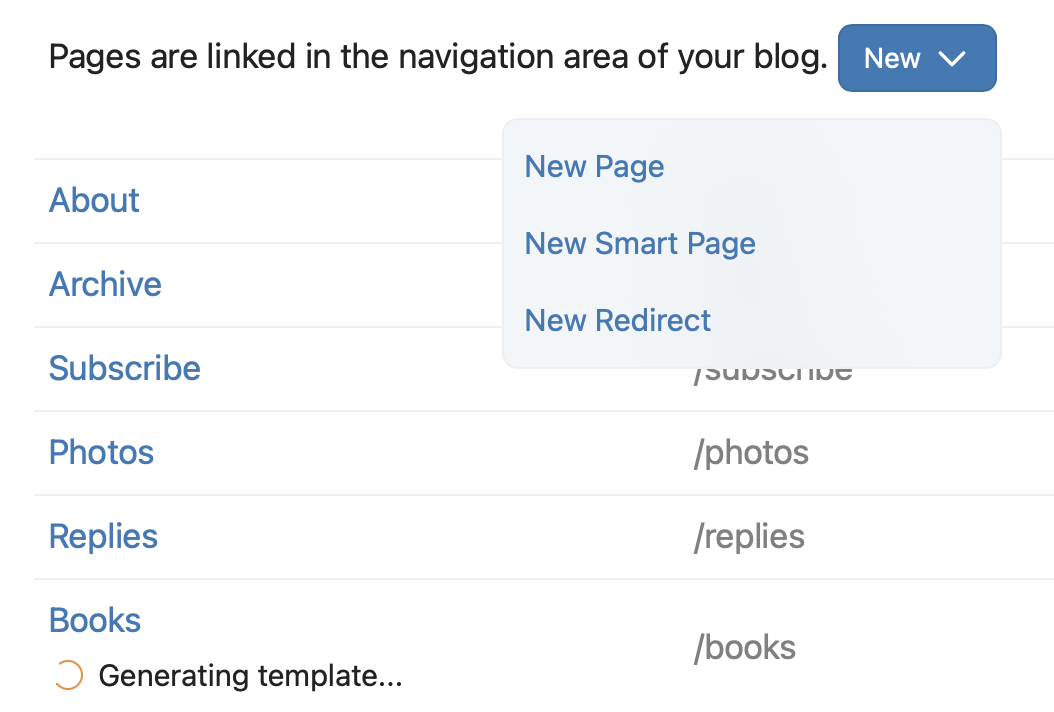

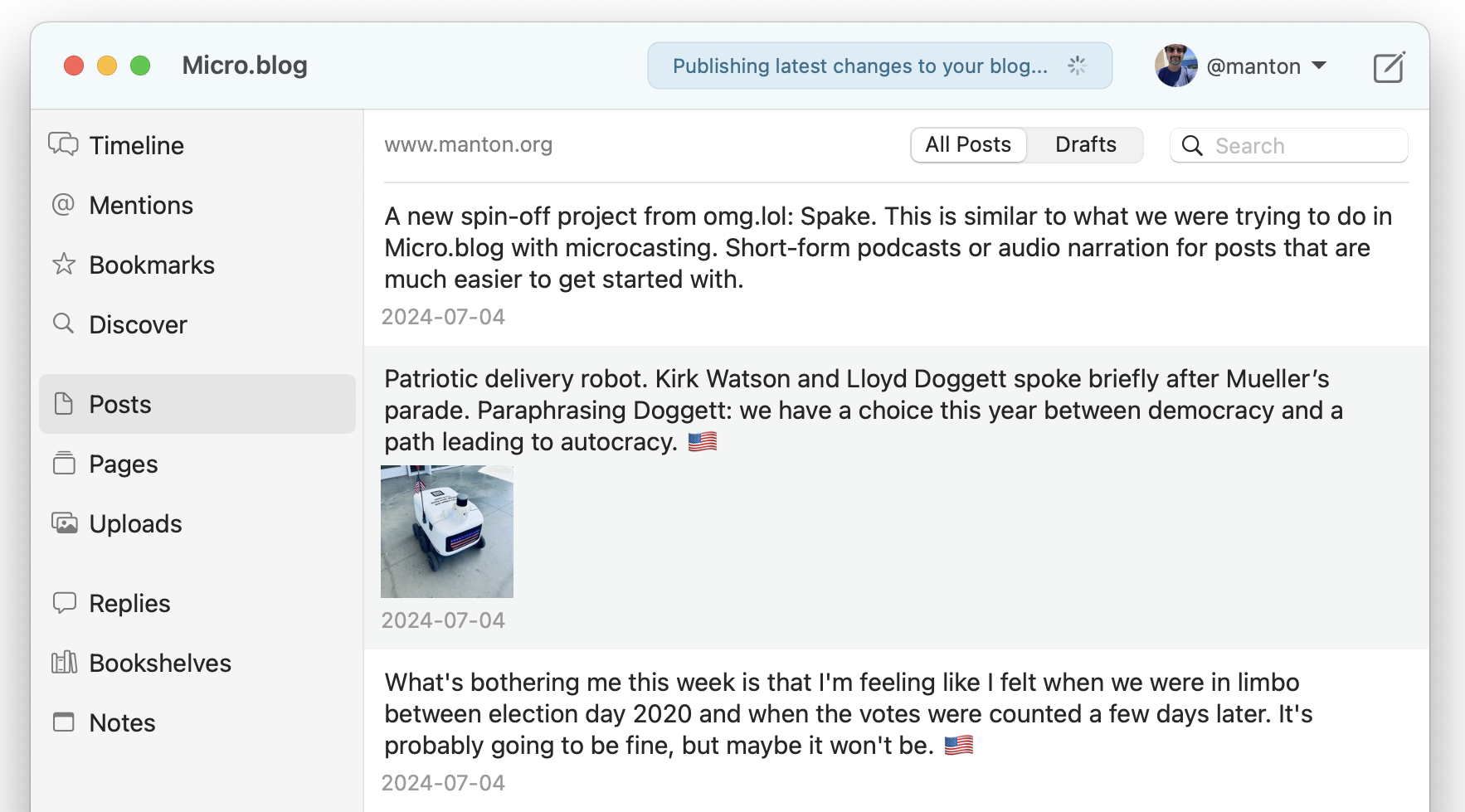

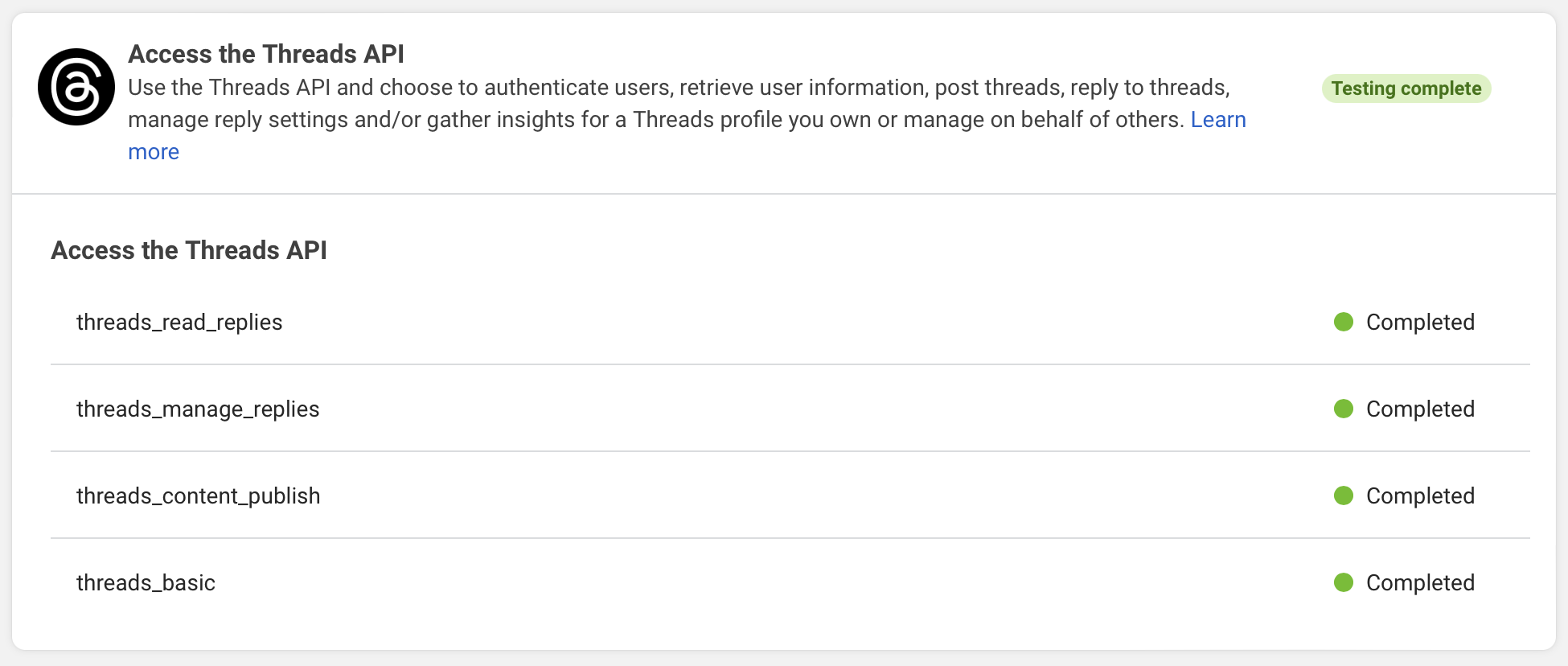

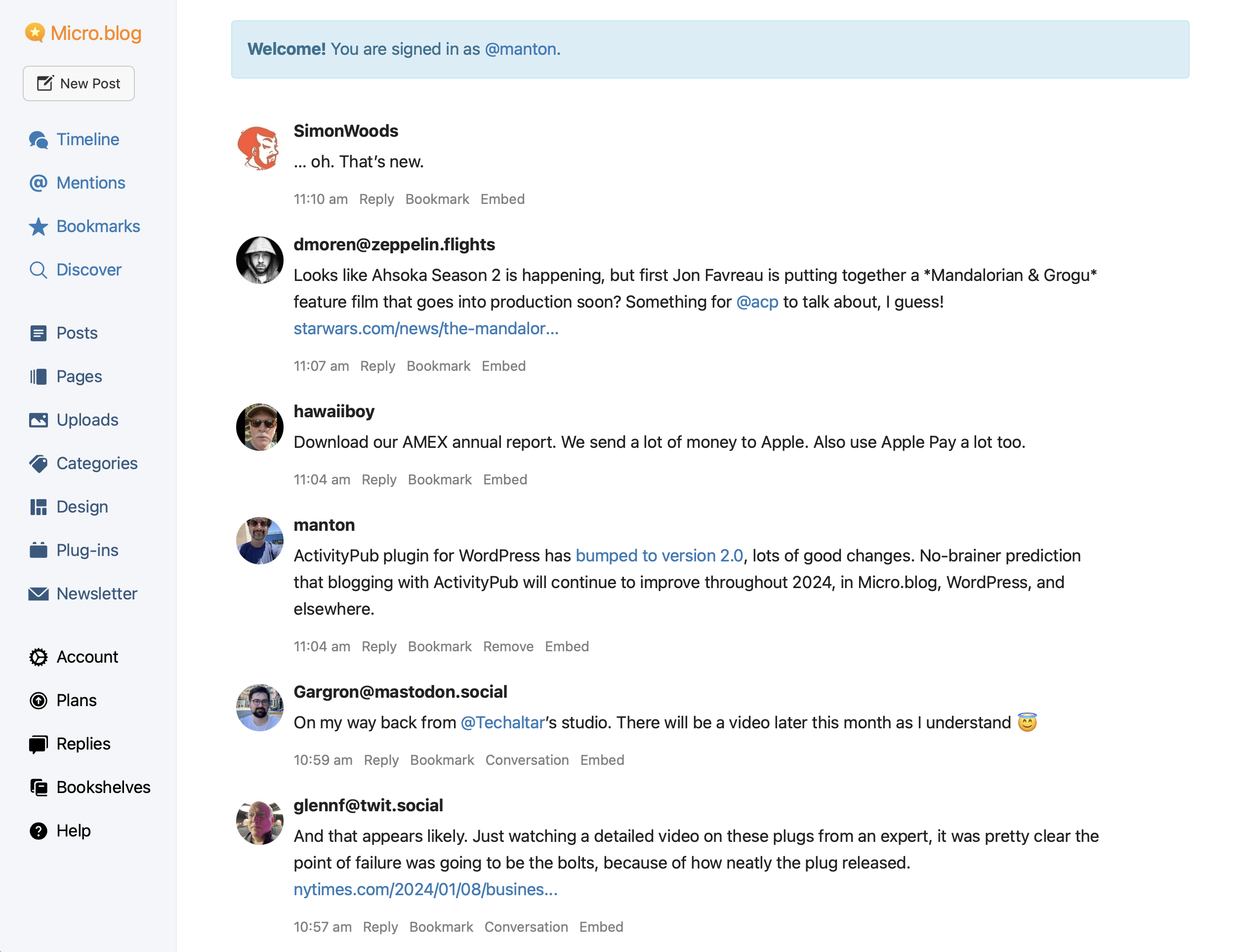

I don’t have answers to these questions. But I love building software for the web. I love working on Micro.blog and making it easier for humans to blog. Generative AI is a tool I’ll use when it makes sense, and we should continue discussing how it should be trained and deployed, while preserving the openness that makes the web great.